"I say yes to participating because I wanted to see an improvement in my quality of life and help other guys with prostate enlargement.”

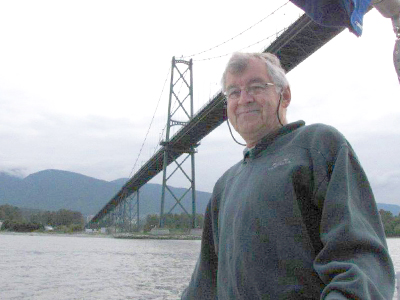

– Lloyd LeBlanc, Sechelt

It was a reality Lloyd LeBlanc had learned to live with. At night, he would wake up to relieve himself every two hours. During the day, he would have to run to a washroom or wait with the discomfort of not being able to urinate at all. LeBlanc’s enlarged prostate had, in short, taken over his life.

“Traveling and changes in routine were often issues,” says the 74-year-old retired accountant. “At work, we would be in meetings sometimes and I would have to go to the washroom before the break.”

LeBlanc was in his 50s when he first noticed symptoms of prostate enlargement. He had difficulty urinating, and when he did it was often accompanied by a burning sensation and an inability to completely empty his bladder.

As his condition progressed, LeBlanc increasingly had the need but not the ability to go, and would have to sit down and wait until he could. At other times, he would urgently need to find a washroom or, in desperation, a bush.

“You get to know where to find a bathroom wherever you’re going. If you go to a store, you have to find a bathroom.”

On top of the inconvenience, there was a growing risk that an ongoing backup of urine in his bladder could damage LeBlanc’s kidneys.

His longtime urologist—Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) scientist Dr. Larry Goldenberg—asked LeBlanc if he was interested in participating in a clinical trial to treat his enlarged prostate. It was for a novel approach called the AQUABEAM Robotic System that combines multi-dimensional imaging, robotics and heat-free waterjet ablation for targeted, personalized and immediate removal of prostate tissue. LeBlanc unconditionally agreed.

Finding the right approach to treat a common condition

Almost all men will experience some form of prostate enlargement by age 60, according to the Canadian Cancer Society.

The condition, technically called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), is usually part of the natural aging process. It is non-cancerous and only becomes problematic when it causes adverse symptoms, such as kidney, bladder and urinary tract problems. In severe cases, a man’s prostate may grow so large that it cuts off the flow of urine completely.

In British Columbia, there were 4,360 prostatectomies performed for benign prostatic enlargement in 2014/2015.

Treatment for BPH ranges from lifestyle changes to medication and surgery. There are many surgical approaches—the most common of which is the transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) procedure. All involve removing prostate tissue that is blocking the flow of urine.

LeBlanc was among three men who participated in the Vancouver arm of a clinical trial and received the Aquablation therapy. The study was facilitated at the VCHRI Clinical Research Unit. A small telescope was inserted through their urethras and high-pressure water jets were used to remove enlarged prostate tissue while sparing nearby structures, such as the neck of the bladder and urinary sphincter.

“Now I don’t have to get up in the night at all to go to the bathroom. I can quickly empty my bladder and know that my bladder is completely empty.”

Dr. Ryan Paterson, a VCHRI researcher and vice-chair of Clinical Operations at the UBC Department of Urologic Sciences, says the clinical trial highlighted the importance of further integrating diagnostic and therapeutic ultrasound technology into their clinical practice.

“Greater access to and use of ultrasound technology means we could remove targeted tissue, lowering the risk of potential damage to the bladder, ejaculatory ducts and urinary sphincter,” states Paterson.

With his newfound freedom from the symptoms of an enlarged prostate, LeBlanc has more time to go sailing and camping, and to work on projects for his wife’s interior design business—reupholstering couches, installing window blinds and doing some accounting too. He is also looking for a bathroom much less often.

“Now, when my wife and I go down to the beach after dinner with a bottle of wine to watch the sun go down, I don’t need to go to the bathroom after every glass,” LeBlanc says with a smile.

THIS IS ONE PATIENT’S STORY OF PARTICIPATING IN A CLINICAL TRIAL. YOUR EXPERIENCE MAY DIFFER. LEARN MORE ABOUT CLINICAL TRIALS BEFORE PARTICIPATING.