Discovery debunks previously held notions about gene mutations and cancer.

It is a condition that affects one in 10 girls and women during their reproductive years, and VCH Research Institute researcher Dr. Michael Anglesio and colleagues have uncovered new clues about how it affects cells in the body.

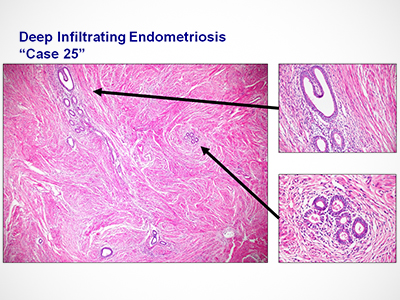

Endometriosis is the development of uterine-lining tissues outside the uterus. It is often associated with pelvic pain, heavier periods and sometimes infertility. It is a benign condition and exceptionally common, but can also be a precursor to the development of cancer in rare cases.

“Around one million Canadian girls and women have endometriosis, but only 0.5 per cent will develop ovarian cancer.”

Anglesio has been interested in studying endometriosis lesions that lead to cancer since joining the OVCARE team in 2010. He wanted to know why endometriosis sometimes does not turn into cancer.

(Back L-R) Niki Boyd, Basile Tessier-Cloutier, Amy Lum, Julie Ho, Natasha Orr, Vivian Lac. (Front L-R) Paul Yong, Michael Anglesio, David Huntsman, Janine Senz.

Photo by Dr. Tony Karnezi

When a colleague, Dr. Paul Yong, approached him with several endometriosis specimens and a similar interest in uncovering what was going on in non-cancerous endometriosis cells, Anglesio jumped at the opportunity. “We wondered if non-cancerous endometriosis samples had similar mutations to those in cancer cases where endometriosis was present,” says Anglesio.

“We discovered that the same kinds of mutations were present in both cancerous and non-cancerous cases.”

This discovery runs counter to the prior belief that certain mutations in endometriosis cells would lead to cancer. In other words, Anglesio notes, “it was believed that any mutations in endometriosis were driving malignant transformation.” In the long-term, this research could also shed light on whether some gene mutations in endometriosis are indeed precursors to ovarian-related cancer.

Research shows that endometriosis cells can behave like cancerous ones

For their paper, “Cancer-associated mutations in endometriosis without cancer,” Anglesio and colleagues analyzed DNA in endometriosis tissue samples and the findings from two independent research teams.

The teams analyzed 39 deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions—a type of endometriosis lesion that invades an organ more than five millimetres below the surface of the tissue. They found that the exact same mutation in cells was being propagated to other parts of the body in the form of new endometriosis lesions. This told the researchers that the endometriosis was somehow able to move, a characteristic normally only seen in cancer and known as metastasis.

Despite this, the mutated endometriosis cells were not strongly correlated with cancer. Cancer-driving mutations were discovered in 10 of the 39 non-malignant lesions—far more cases than would be expected if the mutations resulted in the endometriosis becoming cancerous. This points to the fact that mutations can be present in both cancerous and non-cancerous endometriosis.

“We have only recently made this discovery, and now we know that we have to develop new ways to screen for endometriosis that could potentially become malignant,” says Anglesio.

“This is the first step to developing screening for endometriosis or endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers. We know that we need to look at indicators other than just gene mutations. As such, we are working with surgeons to find ways to access tissue samples and create a new classification system for endometriosis.”