Prostate cancer researchers find new target for drug therapy.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men. While incidences of the disease are declining, roughly 21,000 Canadian men are still diagnosed each year, with 1 in 29 cases taking an aggressive and deadly form. At the Vancouver Prostate Centre (VPC), Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientists, Dr. Artem Cherkasov and Dr. Paul Rennie are combining teamwork and state-of-the art technology to try to bring those numbers down. In their work they focus on the androgen receptor (AR)–a protein that is regulated by male hormones and represents one of the main drivers of prostate cancer.

"Prostate cancer tumours need androgen receptors to live and progress. If you can shut down these receptors you can eliminate prostate cancer."

Using a computer modelling system that can scan a database of hundreds of millions of molecules, Cherkasov develops virtual anti-AR drug candidates. Then, if they have good potential, he hands them over to Rennie for real-life experimental evaluation. “We first discuss which area of the AR protein to focus in on,” says Rennie. “Art brings the hammer and I tell him where to hit. It is a great partnership.”

Over the years, countless anti-AR drugs have been developed to attack what appears to be a simple, single target. But it is far from simple—AR is incredibly drug-resistant. It mutates rapidly and in the case of progressive prostate cancer, it learns how to outmanoeuvre new drug therapies very quickly.

“It’s like whack-a-mole,” says Rennie. “You hit it down, but it pops up again. In the interim the patient gets several months to a year or so. But it comes back.” In some patients, the mutated AR is even able to use the drug to accelerate cancer growth.

“We know that AR is very capable of mutating. Everything that is on the market has already been countered by those mutations. We hope to bypass that stage.”

The when and where of the attack

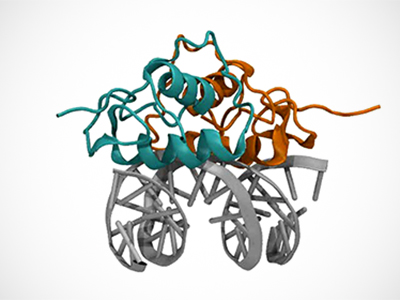

Current anti-AR drugs typically target AR at its early stage of activation, which is a complex and multi-step process. So Rennie and Cherkasov are shifting the timeline. The team has designed a drug compound to attack AR at a later stage of its activation in a cell, called dimerization. Dimerization is when two AR proteins are joined to then become a fully activated AR complex. It is only after this dimerization stage that AR becomes a driver of various biological process including those that regulate the development of prostate cancer.

“No one else has been able to address this stage before,” says Cherkasov. “Using our technology, we are the first to try and target that downstream step. Our approach is showing good results in initial in vitro experiments.”

This new drug prototype also targets a different region of the AR protein than other anti-AR drugs. Rennie calls it the ‘business end’ of the AR, a core region crucial to the protein’s survival and therefore less likely to mutate and cause more aggressive cancer.

“That’s the beauty of it; it can potentially be applicable for even the hard-to-treat cases. And, theoretically, this drug could shrink existing tumours as well as prevent the growth of new ones.”

Cherkasov says having access to the right tools has given his team the leading edge in prostate cancer research—without the aid of his computer models at VPC, he would not have been able to find and target this region of the AR protein. The team plans to move on to pre-clinical testing in the next six months, and hopes for clinical trials of the dimerization compound within two to three years. A summary of their findings is published in the latest edition of Science Direct.