Study suggests that perceptual learning exercises can help prosopagnosia patients recognize faces.

Imagine not recognizing the face of a person you see every day, or even the face of someone you’ve known all your life, like a parent or sibling. Such is the reality for people with prosopagnosia – a selective visual problem caused by damage to the very specific brain circuitry responsible for taking the visual image of a face and recognizing it. Some individuals with prosopagnosia acquired the condition, e.g. due to brain injury or trauma, while others are born with it.

There are currently no effective treatments for prosopagnosia, which is partly why Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute clinician scientist Dr. Jason Barton and his colleagues developed and studied a perceptual learning intervention to see if they could teach prosopagnosia patients to recognize faces.

“The literature on perceptual learning says that with training and sheer practice over and over, you can improve your ability to see details and recognize things at a level you couldn’t before,” explains Dr. Barton, Canada Research Chair in Human Vision and Eye Movement, Marianne Koerner Chair in Brain Diseases, and professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia.

“We wondered whether this would work in prosopagnosic patients with brain damage and whether we could design a training program that would enhance a patient’s ability to see what it is about a face that makes a person recognizable, regardless of whether they’re smiling, frowning or angry, and regardless of whether they’re being viewed straight on, from an angle, or the side.”

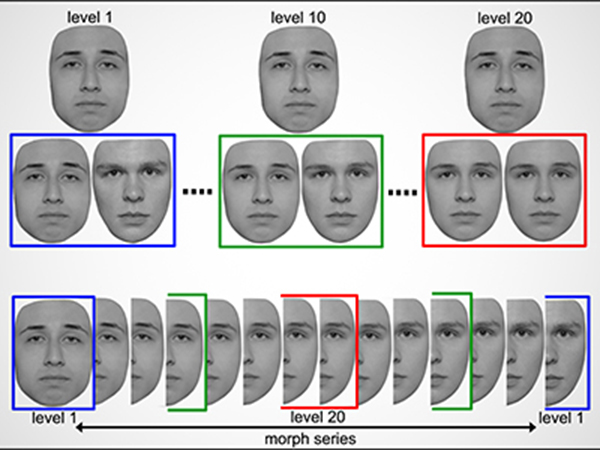

In their recently published paper in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Dr. Barton and his colleagues detail their perceptual learning program, which aimed to train face-blind patients to see slight differences in face shape over a period of 11 weeks or more. The researchers developed a large stimuli set of faces with a variety of emotions and viewpoints. Participants began the program by looking at these different faces straight on. Once they were able to tell the difference between these faces, they graduated to the next level, at which the viewpoint of the faces started to differ more. Once they could do this, they then trained on faces that gradually differed in expression. Eventually, they reached difficult levels where they had to tell the difference between faces when the faces differed in both facial expressions and viewpoints.

Example training trials (top) and selected images from a set of morphed stimuli of an identity pair (bottom). Participants see three faces and indicate which of the bottom two faces most resembles the top face. Difficulty was manipulated by creating a morph continuum of two face identity images (bottom): using as choice faces the images from the far ends of the morph series creates the easiest discrimination level (blue frame, Level 1). Pairing images at the center of the morph series creates the most difficult trial (red frame, Level 20), whereas pairing images located between the center and the end of the spectrum creates a moderately difficult trial (green frame, Level 10).

The study found a 20 to 30 per cent improvement in participants’ ability to see the differences in facial shape within the set of faces on which they trained, even when the testing involved viewpoints and expressions they hadn’t seen during training. Equally important, they also improved by 10 to 20 per cent when they were tested with new faces that were not used during training.

Dr. Barton highlights that while their intervention doesn’t cure prosopagnosia, it offers a promising starting point. Future work will involve imaging studies to see what changes in the brain occur with this learning, and whether the amount of learning can be enhanced through the coupling of training with medications or techniques that promote brain plasticity.

“There’s been a lot of pessimism about the possibility of improving acquired prosopagnosia,” says Dr. Barton. “We’re pleased to be able to show that a structured, simply designed program, albeit with a lot of practice, can actually improve face-blind patients’ ability to see the difference in faces.”